What is Conditioning?

Feb 15, 2022

Conditioning is what happens to us as we grow up with our parents, enter school and join society. Many parents withhold giving love and positive attention to their children unless the child behaves in a way they deem “good.” Yet a child needs to experience unconditional love from its parents, at least for the first few years of its life. This is an innate need, as modern psychology now ensures.

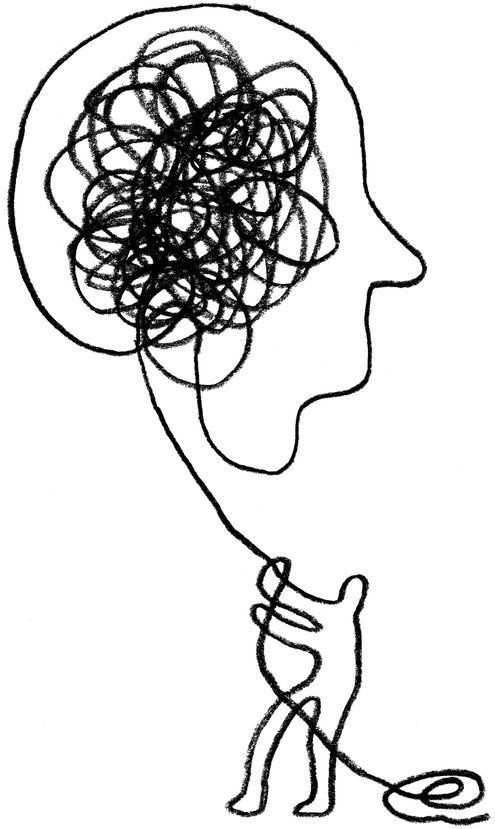

In response to being conditioned to be “good”, children typically develop one of two attitudes. Some become compliant to authority and others resistant. Neither of these are natural. Compliance to authority general leads to “dead spots” in the muscle fascia and resistance to authority manifests as holding patterns of muscular rigidity. These attitudes of compliance or resistance tend to remain throughout our life unless the muscular patterns are worked on.

As the early teenage years begin, and hormonal changes take place, so most of us become highly concerned with how we appear to others. We become hyper-sensitive to other people’s perceptions of us, particularly our peers. We learn in this time that as social beings we have needs. We want to form friendships and join a social group. We want to be attractive to the opposite sex, or same sex. And we want to find a job or social role that makes us feel we’re a part of society. These are natural social needs. How we try to get these needs met is by creating a “persona”, a front through which we can interact with the outside world.

Our brain learns which emotions are “OK” to show, and what aspects need to be hidden or repressed.

Some people learn not to show anger, for example. Anger is our natural emotional response to any perceived sense of invasion (our body, our family, our ideas, our expectations, etc). Yet some learn that showing anger will prevent them from getting their needs met. So they learn to avoid situations where they could get angry – confrontational situations – and they learn to repress anger and not show it. This repression is what creates holding patterns. By constantly not allowing a natural emotional response to be shown so huge holding patterns and dead spots accumulate in the muscle system and are constantly reinforced.

Likewise, others learn not to show pain, to allow vulnerability. Again this is another natural emotional response that is frequently repressed through the belief that showing sadness or pain will prevent us from getting our needs met. Young men in particular often struggle to show pain or allow vulnerability. This is not because it is not present, rather that they believe that they need to maintain a front of invulnerability in order to be “one of the guys” or to attract women. Once again, this refusal to show these feelings becomes huge holding patterns that eventually controls our behavior and blocks our ability to feel vibrantly alive in the moment.

Body sensations are a very powerful tool for the processing of trauma and illness. Often, the memories of early trauma and painful body experience are held only in somatic memory with no words or narratives to make sense of the experiences. These sensations may be accompanied by visual or sensory images of past events and be powerful elicitors of arousal and distress. This is known as non- declarative or episodic memory, and these images and sensations become the targets of trauma processing interventions. Body sensation work becomes a sensitive and powerful way to access these memories and do the emotional processing involved.

Aposhyan, Susan. Embodying Nature. Somatics, 1995-96.

Gendlin, Eugene. The Wider Role of Bodily sense in Thought and Language. In “Giving the Body Its Due” by M. Sheets-Johnstone, 1992 Levine, Peter. Waking the Tiger, 1997, North

Conditioning, in physiology, a behavioral process whereby a response becomes more frequent or more predictable in a given environment as a result of reinforcement, with reinforcement typically being a stimulus or reward for a desired response. Early in the 20th century, through the study of reflexes, physiologists in Russia, England, and the United States developed the procedures, observations, and definitions of conditioning. After the 1920s, psychologists turned their research to the nature and prerequisites of conditioning.

Stimulus-response (S-R) theories are central to the principles of conditioning. They are based on the assumption that human behaviour is learned. One of the early contributors to the field, American psychologist Edward L. Thorndike, postulated the Law of Effect, which stated that those behavioral responses (R) that were most closely followed by a satisfactory result were most likely to become established patterns and to reoccur in response to the same stimulus (S). This basic S-R scheme is referred to as unmediated. When an individual organism (O) affects the stimuli in any way—for example, by thinking about a response—the response is considered mediated. The S-O-R theories of behaviour are often drawn to explain social interaction between individuals or groups.

Conditioning is a form of learning in which either (1) a given stimulus (or signal) becomes increasingly effective in evoking a response or (2) a response occurs with increasing regularity in a well-specified and stable environment. The type of reinforcement used will determine the outcome. When two stimuli are presented in an appropriate time and intensity relationship, one of them will eventually induce a response resembling that of the other. The process can be described as one of stimulus substitution. This procedure is called classical (or respondent) conditioning.

In this traditional technique, which is based on the work of the Russian physiologist Ivan P. Pavlov, a dog is placed in a harness within a sound-shielded room. On each conditioning trial the sound of a bell or a metronome is promptly followed by food powder blown by an air puff into the dog’s mouth. Here the tone of the bell is known as the conditioned (or sometimes conditional) stimulus, abbreviated as CS. The dog’s salivation upon hearing this sound is the conditioned response (CR). The strength of conditioning is measured in terms of the number of drops of saliva the dog secretes during test trials in which food powder is omitted after the bell has rung. The dog’s original response of salivation upon the introduction of food into its mouth is called the unconditioned response (UR) to food, which is the unconditioned stimulus (US).

Instrumental, or operant, conditioning differs from classical conditioningin that reinforcement occurs only after the organism executes a predesignated behavioral act. When no US is used to initiate the specific act to be conditioned, the required behaviour is known as an operant; once it occurs with regularity, it is also regarded as a conditioned response (to correspond to its counterpart in classical conditioning). American psychologist B.F. Skinner studied spontaneous (or operant) behaviour through the use of rewards (reinforcement) or punishment. For example, a hungry animal will respond to a situation in a way that is most natural for that animal. If one of these responses leads to the reward of food, it is likely that the specific response which led to the food reward will be repeated and thus learned. The behaviour that was instrumental in obtaining the reward becomes especially important to the animal. The same type of conditioning can also be applied to an action that allows the animal to escape from or avoid painful or noxious stimuli.

Psychologists generally assume that most learning occurs as a result of instrumental conditioning (such as that studied by Skinner) rather than classical conditioning. Central to all forms of behavioral interaction, however, is the concept that conditioning creates a change in an animal’s behaviour and that the change results in learning.

Satya, Working With Satya

Sources:

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.